There Round the Corner in the Deep

2019 - 2023

The story unfolds around a large settlement in the Nizhny Novgorod region, a closed administrative-territorial entity (ZATO), a city best known as Sarov.

For a long time, the settlement, which took its name from a swampy river, was associated with a site of Orthodox pilgrimage. age. Seraphim ("Flaming") of Sarov, one of the most venerated Orthodox saints, lived there as a hermit and became known for his miracles. He hand-fed a bear, healed gravely ill people, and spent a thousand days and a thousand nights praying on a stone. It is believed that he predicted his death by stating that "his end will be revealed by fire." Later, in the Soviet era, the heroic figure of the wonderworker was replaced by the new protagonist, the nuclear physicist.

For a long time, the settlement, which took its name from a swampy river, was associated with a site of Orthodox pilgrimage. age. Seraphim ("Flaming") of Sarov, one of the most venerated Orthodox saints, lived there as a hermit and became known for his miracles. He hand-fed a bear, healed gravely ill people, and spent a thousand days and a thousand nights praying on a stone. It is believed that he predicted his death by stating that "his end will be revealed by fire." Later, in the Soviet era, the heroic figure of the wonderworker was replaced by the new protagonist, the nuclear physicist.

The story unfolds around a large settlement in the Nizhny Novgorod region, a closed administrative-territorial entity (ZATO), a city best known as Sarov.

For a long time, the settlement, which took its name from a swampy river, was associated with a site of Orthodox pilgrimage. age. Seraphim ("Flaming") of Sarov, one of the most venerated Orthodox saints, lived there as a hermit and became known for his miracles. He hand-fed a bear, healed gravely ill people, and spent a thousand days and a thousand nights praying on a stone. It is believed that he predicted his death by stating that "his end will be revealed by fire." Later, in the Soviet era, the heroic figure of the wonderworker was replaced by the new protagonist, the nuclear physicist.

For a long time, the settlement, which took its name from a swampy river, was associated with a site of Orthodox pilgrimage. age. Seraphim ("Flaming") of Sarov, one of the most venerated Orthodox saints, lived there as a hermit and became known for his miracles. He hand-fed a bear, healed gravely ill people, and spent a thousand days and a thousand nights praying on a stone. It is believed that he predicted his death by stating that "his end will be revealed by fire." Later, in the Soviet era, the heroic figure of the wonderworker was replaced by the new protagonist, the nuclear physicist.

In the late 1940s, the name Sarov disappeared from the maps of the Soviet Union. Remote enough from major population centers but at the same time located close to Moscow, hidden from prying eyes by dense forests, Sarov was chosen as the location for the unfolding Soviet nuclear program. This secret facility became one of the leading development centers of weapons of mass destruction and was known for its design bureau, KB-11.

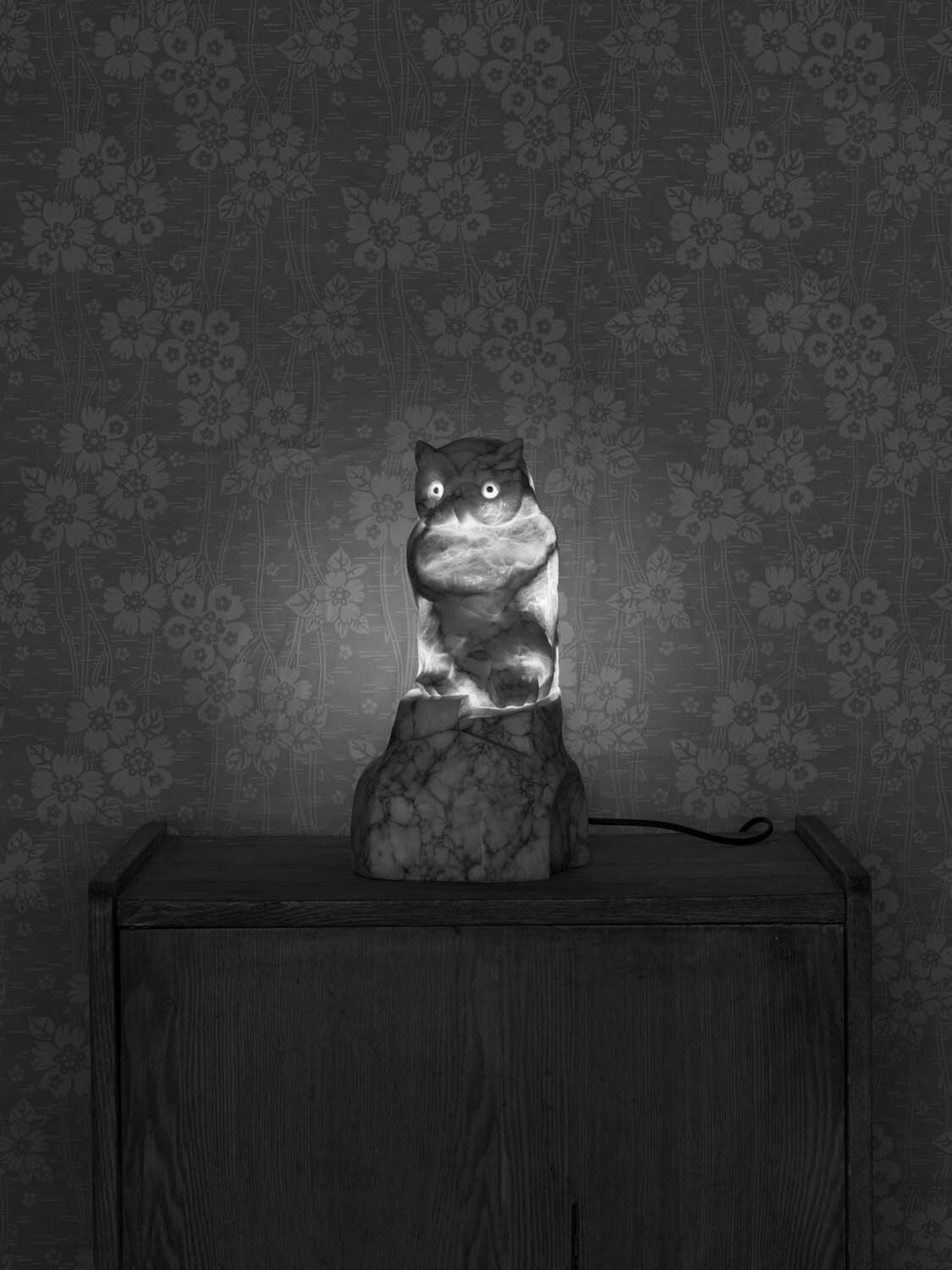

In the decades that followed, the city changed its name, status, and direction of development, taking shape under Soviet ideology, Orthodox myths and legends, and the nuclear weapons program. Now it’s a place where religion and science, faith and militarism are intertwined. The Russian government and the Church use both Orthodoxy and nuclear technology in their propaganda as a symbol of power and oppression. The boundary between fact and fiction becomes less and less visible.

The forest, a central motif throughout the project, acts as both scene and metaphor. Referencing Pasternak’s poetry and the Strugatsky brothers' science fiction, it becomes a symbolic space of the unknown, where memory mutates, histories dissolve, and futures emerge in fragments.

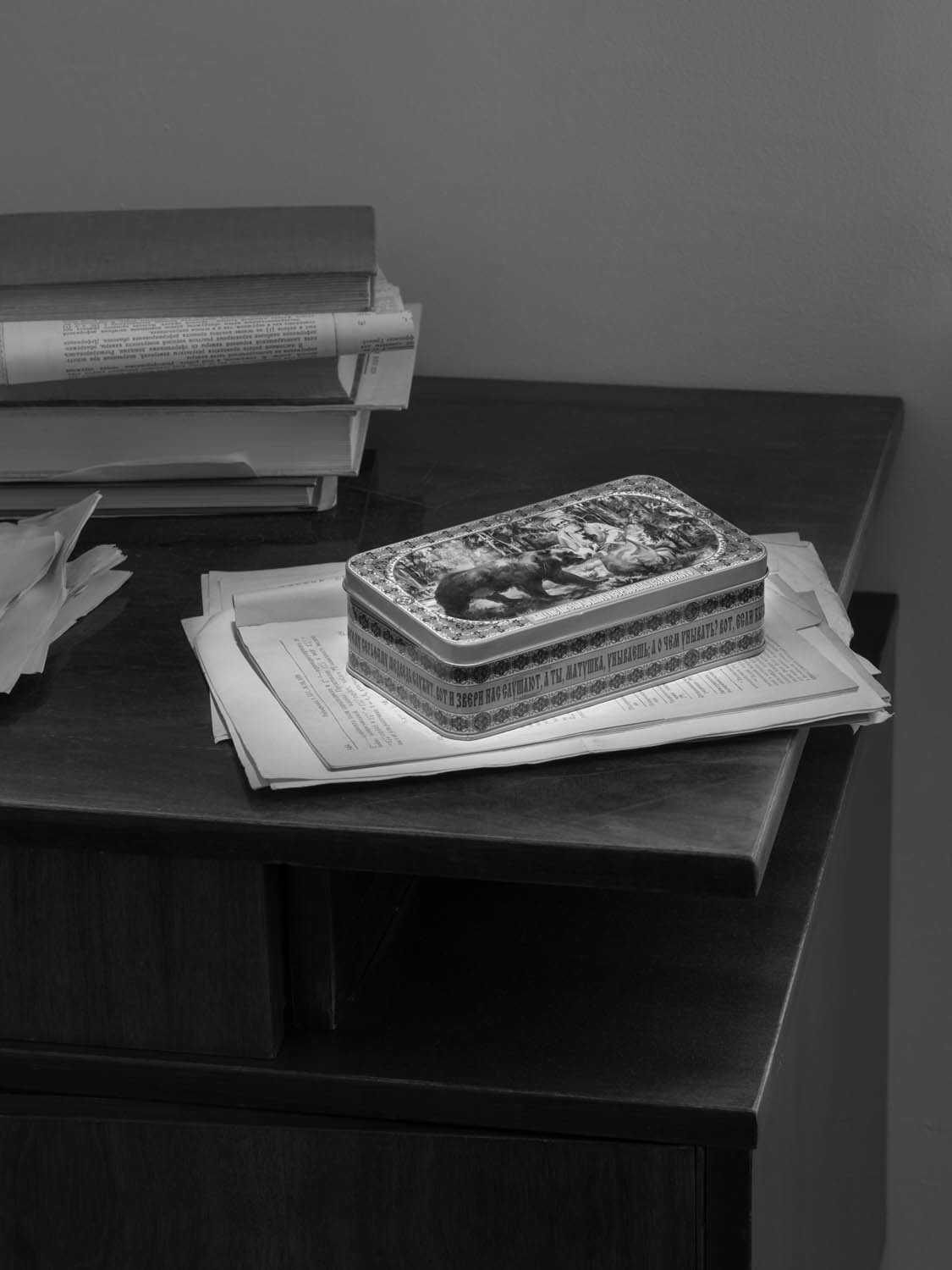

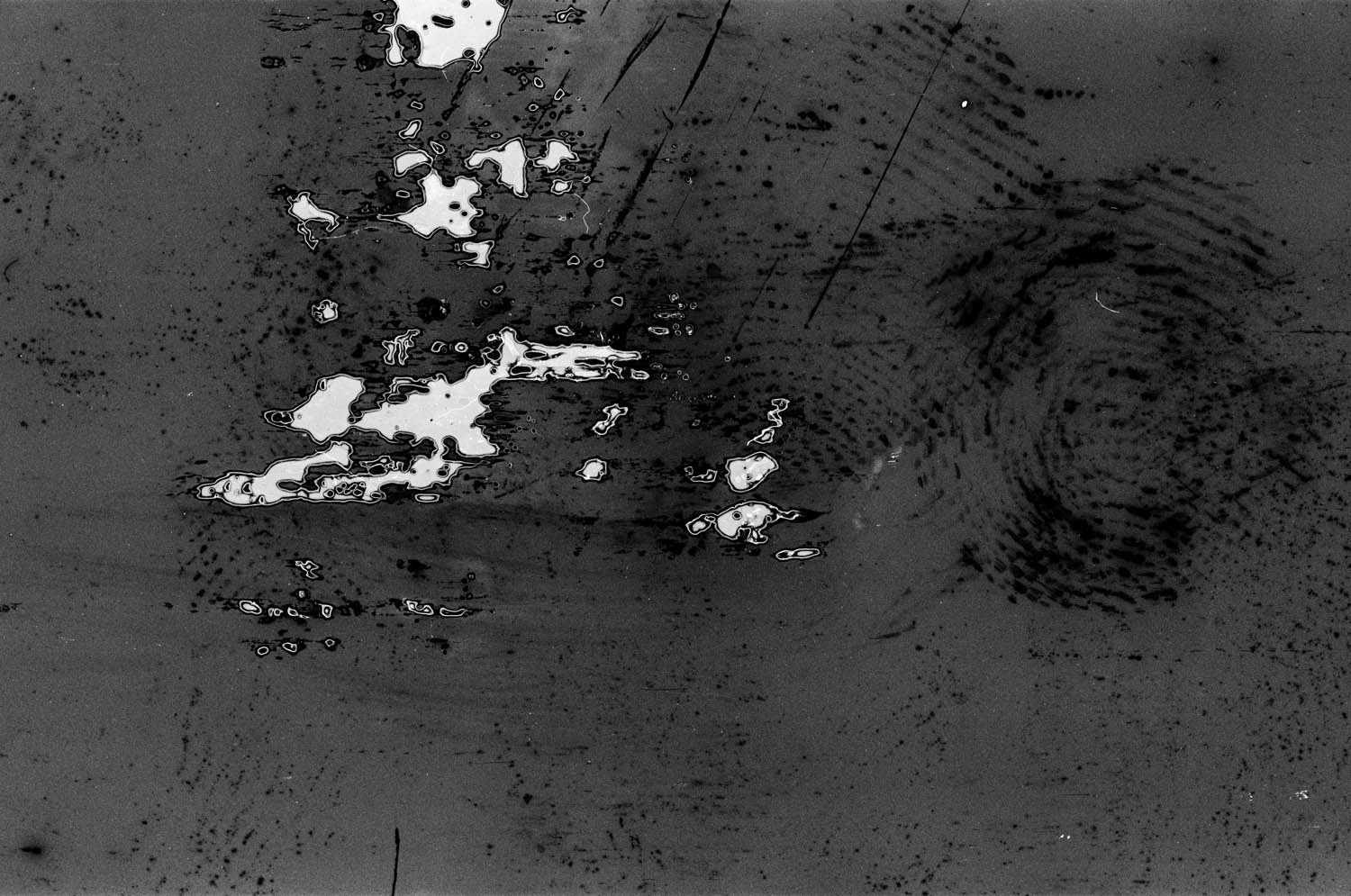

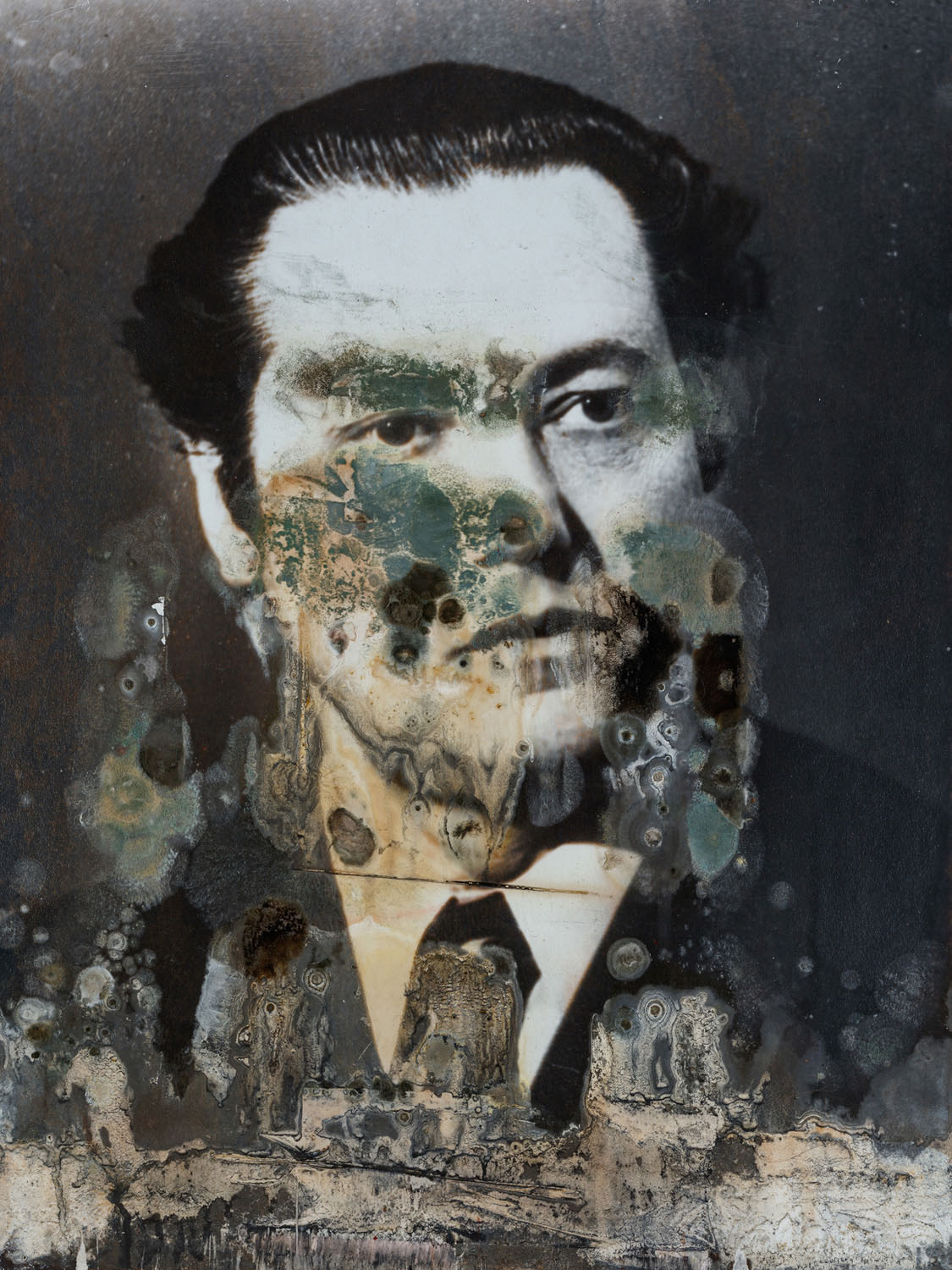

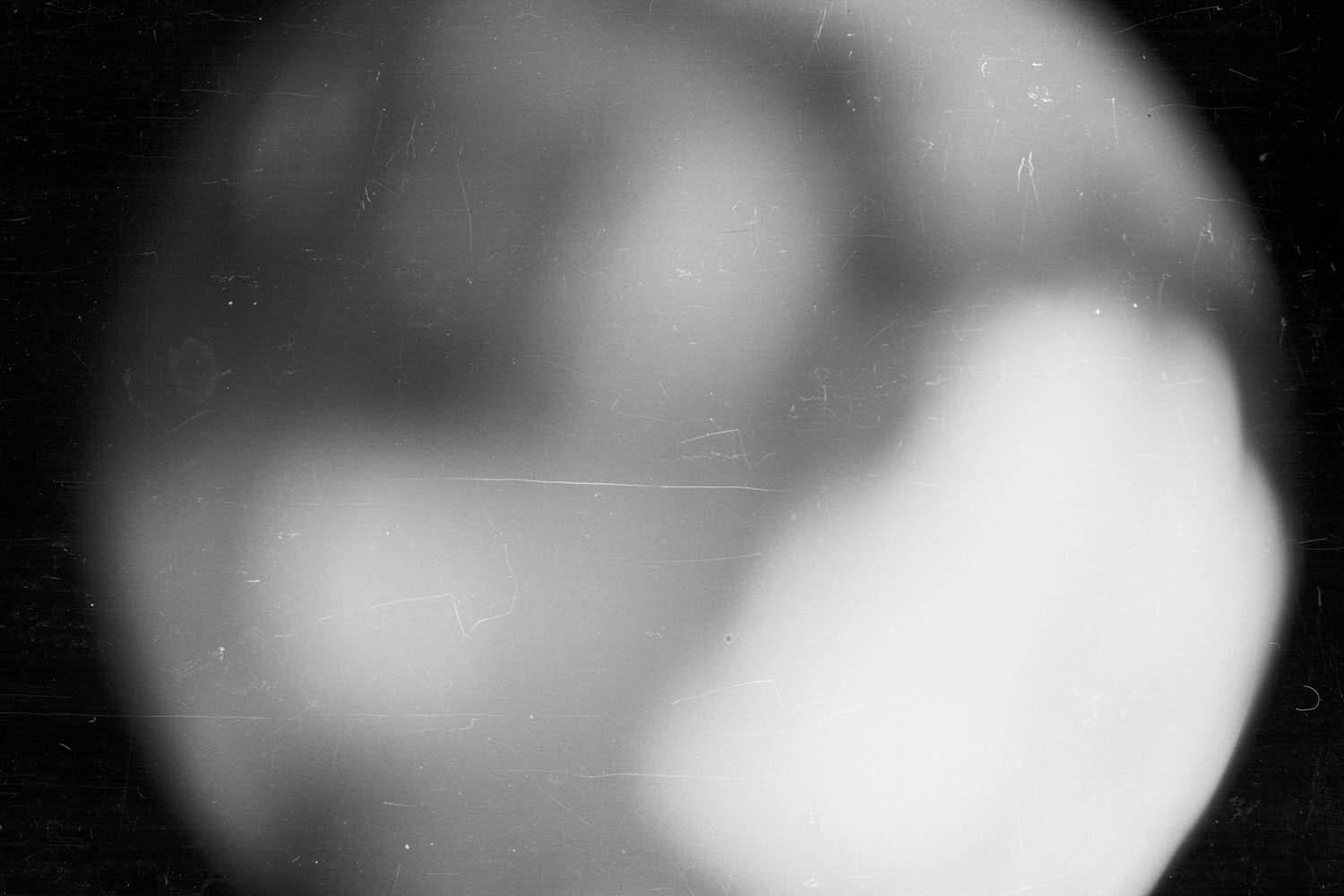

Sarov is still obscured by the trees and bushes, like the Sleeping Beauty’s castle. I went back there, to the house where my grandfather, who worked at KB-11, lived. Like many other young scientists, he thought he would go to the city for a year or two but stayed there for the rest of his life. I never knew him, but inherited his archive of film negatives. Due to strict secrecy, his photographs lack direct documentation, depicting only family and nature, but marked by traces of anxiety—scratches, burnt spots, and mold.

The project is assembled as a speculative archive. I connect a number of time periods and historical contexts, my family history, and the image of a closed city, incorporating pictures from my grandfather's archive, photographs taken by me in and around the city, and staged images based on facts, legends, and speculation. Moldy, spoiled by time, and treated with acid, photographs become a metaphor for the cyclical nature of religious and state imperatives, while the city remains elusive in temporal corrosions of memory.

In the decades that followed, the city changed its name, status, and direction of development, taking shape under Soviet ideology, Orthodox myths and legends, and the nuclear weapons program. Now it’s a place where religion and science, faith and militarism are intertwined. The Russian government and the Church use both Orthodoxy and nuclear technology in their propaganda as a symbol of power and oppression. The boundary between fact and fiction becomes less and less visible.

The forest, a central motif throughout the project, acts as both scene and metaphor. Referencing Pasternak’s poetry and the Strugatsky brothers' science fiction, it becomes a symbolic space of the unknown, where memory mutates, histories dissolve, and futures emerge in fragments.

Sarov is still obscured by the trees and bushes, like the Sleeping Beauty’s castle. I went back there, to the house where my grandfather, who worked at KB-11, lived. Like many other young scientists, he thought he would go to the city for a year or two but stayed there for the rest of his life. I never knew him, but inherited his archive of film negatives. Due to strict secrecy, his photographs lack direct documentation, depicting only family and nature, but marked by traces of anxiety—scratches, burnt spots, and mold.

The project is assembled as a speculative archive. I connect a number of time periods and historical contexts, my family history, and the image of a closed city, incorporating pictures from my grandfather's archive, photographs taken by me in and around the city, and staged images based on facts, legends, and speculation. Moldy, spoiled by time, and treated with acid, photographs become a metaphor for the cyclical nature of religious and state imperatives, while the city remains elusive in temporal corrosions of memory.

In the late 1940s, the name Sarov disappeared from the maps of the Soviet Union. Remote enough from major population centers but at the same time located close to Moscow, hidden from prying eyes by dense forests, Sarov was chosen as the location for the unfolding Soviet nuclear program. This secret facility became one of the leading development centers of weapons of mass destruction and was known for its design bureau, KB-11.

In the decades that followed, the city changed its name, status, and direction of development, taking shape under Soviet ideology, Orthodox myths and legends, and the nuclear weapons program. Now it’s a place where religion and science, faith and militarism are intertwined. The Russian government and the Church use both Orthodoxy and nuclear technology in their propaganda as a symbol of power and oppression. The boundary between fact and fiction becomes less and less visible.

The forest, a central motif throughout the project, acts as both scene and metaphor. Referencing Pasternak’s poetry and the Strugatsky brothers' science fiction, it becomes a symbolic space of the unknown, where memory mutates, histories dissolve, and futures emerge in fragments.

Sarov is still obscured by the trees and bushes, like the Sleeping Beauty’s castle. I went back there, to the house where my grandfather, who worked at KB-11, lived. Like many other young scientists, he thought he would go to the city for a year or two but stayed there for the rest of his life. I never knew him, but inherited his archive of film negatives. Due to strict secrecy, his photographs lack direct documentation, depicting only family and nature, but marked by traces of anxiety—scratches, burnt spots, and mold.

The project is assembled as a speculative archive. I connect a number of time periods and historical contexts, my family history, and the image of a closed city, incorporating pictures from my grandfather's archive, photographs taken by me in and around the city, and staged images based on facts, legends, and speculation. Moldy, spoiled by time, and treated with acid, photographs become a metaphor for the cyclical nature of religious and state imperatives, while the city remains elusive in temporal corrosions of memory.

In the decades that followed, the city changed its name, status, and direction of development, taking shape under Soviet ideology, Orthodox myths and legends, and the nuclear weapons program. Now it’s a place where religion and science, faith and militarism are intertwined. The Russian government and the Church use both Orthodoxy and nuclear technology in their propaganda as a symbol of power and oppression. The boundary between fact and fiction becomes less and less visible.

The forest, a central motif throughout the project, acts as both scene and metaphor. Referencing Pasternak’s poetry and the Strugatsky brothers' science fiction, it becomes a symbolic space of the unknown, where memory mutates, histories dissolve, and futures emerge in fragments.

Sarov is still obscured by the trees and bushes, like the Sleeping Beauty’s castle. I went back there, to the house where my grandfather, who worked at KB-11, lived. Like many other young scientists, he thought he would go to the city for a year or two but stayed there for the rest of his life. I never knew him, but inherited his archive of film negatives. Due to strict secrecy, his photographs lack direct documentation, depicting only family and nature, but marked by traces of anxiety—scratches, burnt spots, and mold.

The project is assembled as a speculative archive. I connect a number of time periods and historical contexts, my family history, and the image of a closed city, incorporating pictures from my grandfather's archive, photographs taken by me in and around the city, and staged images based on facts, legends, and speculation. Moldy, spoiled by time, and treated with acid, photographs become a metaphor for the cyclical nature of religious and state imperatives, while the city remains elusive in temporal corrosions of memory.

Review by Olga Bubich

The book was nominated for the Encontros da Imagem 2023 - Photobook Award and is among winners of Photobook Award by the Photometria International Photography Festival

Special edition of 15 with handmade elements printed on film, silver qelatin prints on the book cover, archival carbon paper (USSR)

Edition: 2022

Language: English

Paper interior: Munken Lynx Rough 120 gsm

Cover material: PERGRAPHICA® Infinite Black 300 gsm

Dimensions: 180 x 240 mm

Amount of pages: 128 pages

Out of stock

Special edition of 15 with handmade elements printed on film, silver qelatin prints on the book cover, archival carbon paper (USSR)

Edition: 2022

Language: English

Paper interior: Munken Lynx Rough 120 gsm

Cover material: PERGRAPHICA® Infinite Black 300 gsm

Dimensions: 180 x 240 mm

Amount of pages: 128 pages

Out of stock